Recent histories have been increasingly interested in the ways in which humanitarian practices, discourses, norms and emotions have been shaped by gendered constructions and hierarchies. The aim of our third session was to take stock of some of these recent historiographical contributions and discuss, through for stimulating papers, how key concepts, such as ‘care’, ‘intimacy’ and ‘experience’, can be mobilised to better understand humanitarian norms, identities, and emotions during the ‘long’ Second World War.

Anne Jusseaume (Lecturer Université d’Artois, Arras) chaired this rich session, attended by 29 participants on 1 February. Bringing her expertise on health, religious communities, gender and material culture to the table, she invited speakers to reflect on the concept of care (Gilligan, 1982) in wartime. Did ‘care’ help communities hold together during the ‘long’ Second World War? Did practices of care contributed in making gender norms evolved or, on the contrary, in fixing gender assignations? For Anne, this concept is particularly useful to reconsider the notion of vulnerability especially in wartime.

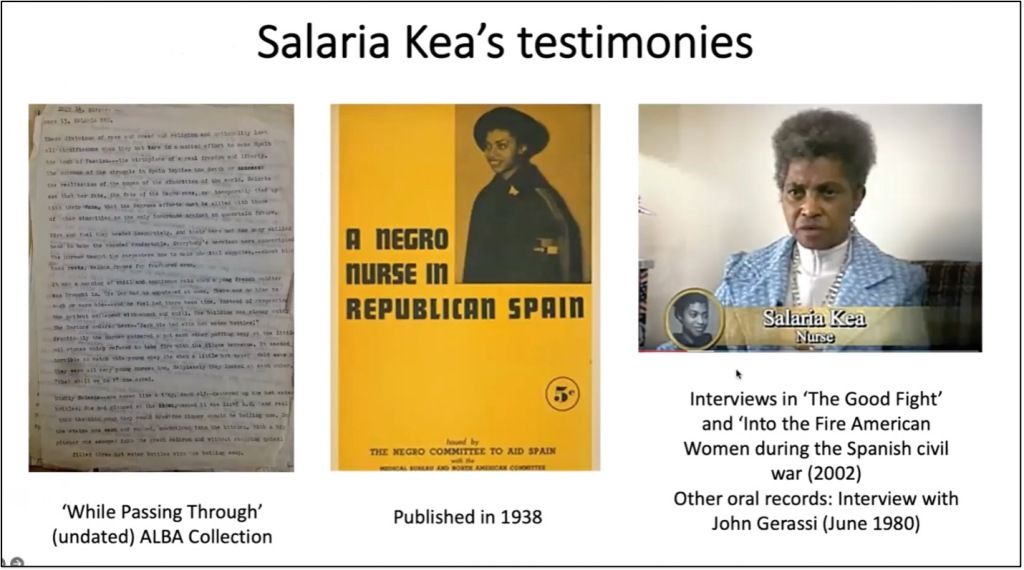

Dolores Martín-Moruno (Université de Genève)started the session with a fascinating paper on the experience of an African American nurse, Salaria Kea, who considered humanitarianism as ‘a manner of struggling for retributive justice’. For Dolores, her autobiographical account A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain published in 1938, challenges us to consider how it felt to be an Afro-American female nurse during the Long Second World War. Drawing on Boddice and Smith’s work (2020) and using experience as an analytical category, Dolores shed lights on the manners in which Key negotiated, what Dolores called, ‘the transnational politics of hate’ caried out by groups such as KKK or the fascists movements and states Dolores concluded her paper by showing how Kea self-fashioned herself as a ‘revolutionary model’, in opposition to the essentialist vision of the female nurse as ‘loving angel’ circulated in the American press. For Dolores, Kea’s experiences allow us to better understand the transnational networks established by the Afro-American community in Europe and the emotions which shaped the identity of the Nord American Bureau and the Negro Committee organisations, in particular, ‘resentment, sympathy, love and hope’.

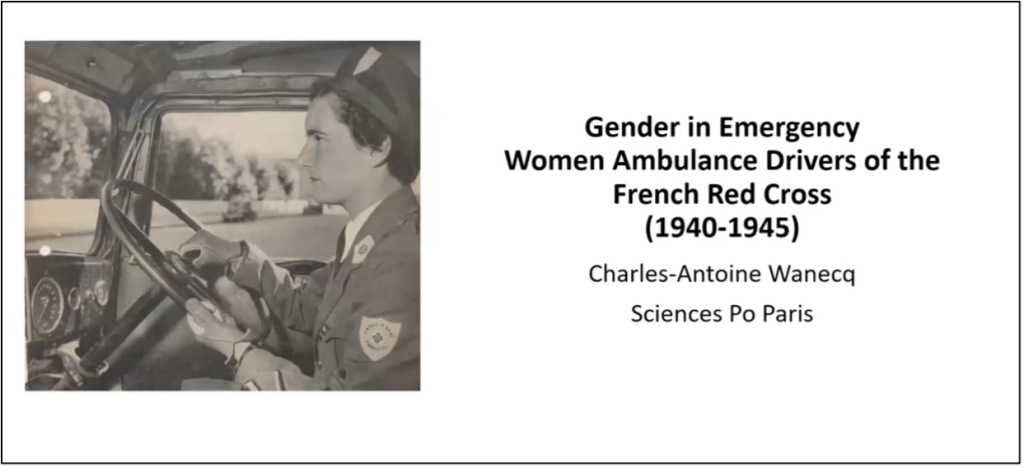

In his paper on French Red Cross Ambulance Drivers from the Sections Automobiles Sanitaires (SAS), Charles-Antoine Wanecq (Sciences Po Paris) turned his attention to the experiences of female humanitarians, whose backgrounds and positions were diametrically opposed to that of Salaria Key. Drawing on the archives of the complex network of French Red Cross societies and personal testimonies, he traced how these bourgeois and aristocratic women contributed to the femininization of a hitherto masculine activity. Often embracing a conservative vision of the role of woman as ‘natural carer’, they saw their work as a vocation (and their job as that of a watchful nurse and careful mechanics). Charles-Antoine concluded by reflecting on the legacies of their wartime activities and efforts at legitimatising their skills in the conservative world of wartime medicine. Often presenting themselves as emergency and first-aid specialist, they were pioneers in the codification of the professionalisation of the position of ambulance driving in France in the 1960s and 1970s.

In his paper, Boyd van Dijk (McKenzie Fellow, Mellbourne Law School)tackled an important, yet surprisingly under-examined question: What roles did gender and sexuality play in the making of the 1949 Geneva Conventions? Boyd challenged widespread assumptions about humanitarian law as a historically progressive endeavour and about the 1949 Geneva Conventions as a legal document that outlawed sexual violence ‘internationally and universally’. He argues instead that the Conventions should be seen as a product of retrograde sexual politics and the result of drafters’ efforts at restoring pre-war gender and sexual norms. Whereas today advocates see rape as a supreme moral concern, the predominantly male drafters showed little interest in it, and did nothing to acknowledge its victims’ suffering. This raises critical questions, not just regarding the extent to which drafters’ sexual politics overlaps with reactionary agendas today, but also to whether the widely-celebrated Conventions remain a useful instrument for campaigns against sexual violence, given their regressive impulses.

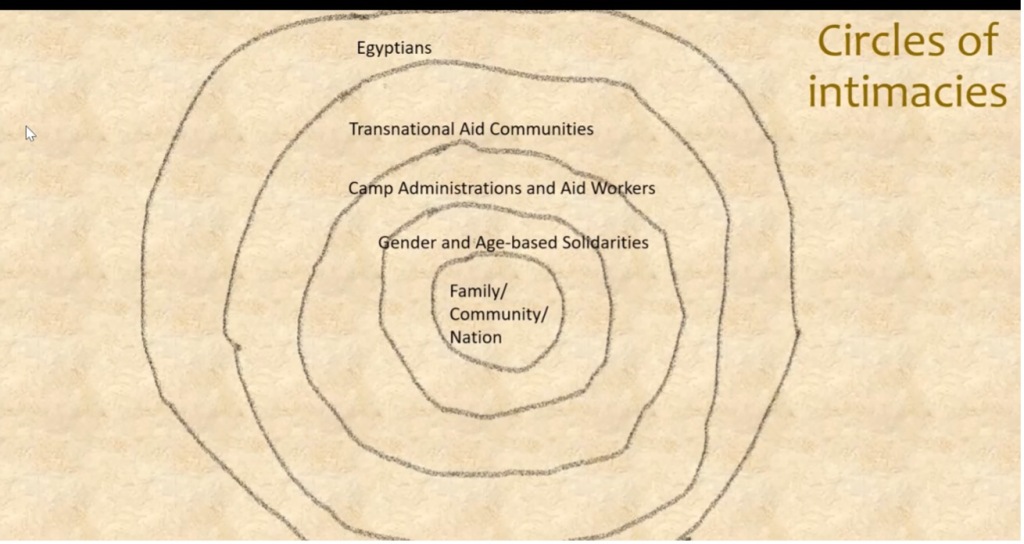

Esther Möller (Universität der Bundeswehr München) and Katharina Stornig (Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen) concluded this captivating session by a paper entitled ‘(U)nsettling Intimacies: Gender and Age in a North-African Refugee Camp, 1944-1946’. They proposed the concept of ‘circles of intimacies’, defined as ‘circles of (presumed, attempted or prevented) human bonding and closeness’ to better understand social relations amongst Yugoslavian refugees within the camp of El Shatt (Egypt). Examining both the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration [UNRRA] administration and refugees’ self-organization, Esther and Katharina demonstrated how gender and age were fundamental for the imagination and organization of closeness and distance in this international community – intimacy being both a condition and a product of humanitarian aid and of the different relationships established and maintained in the camp. They also challenge us to reflect on the ‘absent’ circles of the Egyptians, who have left very little traces in UNRRA archives.

These thought-provoking papers were followed by a stimulating discussion about material culture and the insights that historians of humanitarianism could gain by examining ‘gendered objects’ (such as ambulances). We also came back to the question of the war as a rupture and a ‘moment of experimental freedom’.

Further reading:

Rob Boddice and Mark Smith ‘Emotion, Sense, Experience’, Elements in Histories of Emotions and Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Boyd van Dijk Preparing for War: The Making of the Geneva Conventions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

Dolores Martín-Moruno, Brenda Lynn Edgar and Marie Leyder ‘Feminist perspectives on the history of humanitarian relief (1870-1945)’, Medicine, Conflict and Survival, Vol. 36, No. 1 (2020), pp. 2-18.

Esther Möller, Johannes Paulmann and Katharina Stornig (ed) Gendering Global Humanitarianism in the Twentieth Century (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Charles Antoine Wanecq ‘Entre le transporteur et l’infirmière: conflits de genre autour de la definition d’un care ambulancier (1939-1973), in Anne Hugon, Clyde Plumauzille, Mathilde Rossigneux-Meheust ‘Le travail de care’, Clio, Femmes, Genre, Histoire, Vol. 49 (2019), pp. 115-136.