We held our second seminar on ‘Race, Military Psychiatry and Mental Health’ on 11 January. Chaired by Guillaume Lachenal (Sciences Po), the aim of this seminar was to discuss how specific racial, gendered and environmental tropes fed into psychiatric discourses and practices in the era of the ‘long’ Second World War. The seminar was attended by 20 participants, mainly drawn from the UK, France and Australia. The three papers ranged geographically from the United States to North Africa and traced the ways in which military authorities constructed mental health diseases and essentialist theories about the ‘other’.

In the first paper, Élodie Edwards-Grossi (Université Paris-Dauphine) considered the treatment of African American troops, who represented 11% of all men liable for service in the US army during WW2. She demonstrated that military authorities used psychiatry to justify segregation through biological, cultural and social essentialization. Such stereotypes went back to the American Civil War, when white officers considered African American soldiers as ‘too much animal to have moral courage or endurance’ as historian Margaret Humphreys has shown. Élodie also examined African-Americans’ responses to the injustices and humiliation they faced: they were asked to sacrifice themselves for a nation that denied their humanity. She concluded that the racial question was constructed by psychiatrists as a public problem relating to group cohesion over and above the issue of social class. According to her, psychiatric expertise was caught between two conflicting prerogatives: on the one hand, the need to call on African American troops and encourage cohabitation; on the other hand, the necessity to justify segregation and ‘confirm’ southerners’ assumptions about the supposedly natural and/or cultural instability of blacks as well as their hypermasculinity.

In the following paper, Julie Le Gac (Université Paris Nanterre) addressed the issue of colonial soldiers’ war neuroses and their approach by the French army during World War Two – demonstrating that psychiatric diagnosis and treatment participated in the construction of “colonial alterity”. At the time, she said, the French reviving army relied so heavily on colonial soldiers that the Algiers school shaped French military psychiatry. Their otherness was thought of through European standards, with military doctors establishing a hierarchy between people based on theories of psychological development and relegating colonial soldiers to primitivism. Highlighting the paradoxes and contradictions of such an essentialization, Julie showed that in the eye of the French military, battle stress and war neuroses manifested themselves differently among colonial soldiers because of supposed characteristics. Their sincerity was, for example, often called into question, while the expression of superstitions were pointed out as specific to them – medical discourse tended to privilege cultural and environmental explanation over racial arguments.

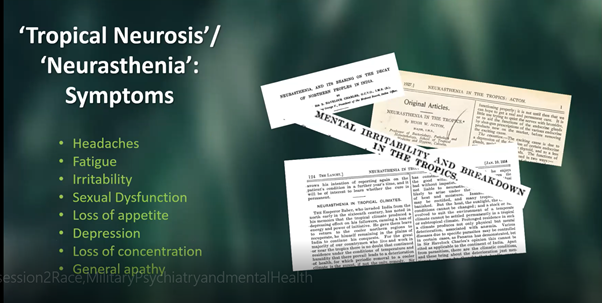

In the third paper, Frances Houghton (University of Manchester) focused on the medical construction of ‘tropical neurosis’ as a disease affecting white Europeans in colonial territories and its expression in Britain’s Royal Navy service as late as 1944/1945. She demonstrated that such diagnosis derived from ‘tropical neurasthenia’, identified at the end of the 19th century. Though heavily debated during the interwar period, this diagnosis experienced a distinct renaissance at the end of WW2 – reflecting enduring imperial insecurities and fear about white colonial masculinities. Frances offered fascinating insights into the ‘Report on Living and Working Conditions among R.N. Personnel in the Tropics’ (1944), written by two naval medical officers, persuasively highlighting its assumption about racial ‘whiteness’ and increasing holistic approach towards the mind-body interface. According to these naval experts, poor mental health was as much the result of physical ailments and emotional hardships as congenital weakness. This sheds light on the medical making of paradigms of racial whiteness in naval medicine during the Second World War in that it identifies and legitimises white racial grievances as a threat to mental health.

These fascinating papers were followed by a stimulating discussion on whether the war represented a rupture in colonial and military psychiatry, Guillaume Lachenal provocatively asking whether the war was a ‘moment of decompensation’, when racism was destabilised. We discussed why psychiatrists devoted so much efforts into constructing the ‘other’ and how far this was link to broader attempts at establishing the discipline as a legitimate one (in competition with cultural anthropology) and/or serving the war efforts.

One Reply to “”