Our fourth session focused on American power, resistance to and ‘renegotiation’ of this power. As Andrew Buchanan recently argues in ‘Globalizing the Second World War’ (article available here), the single most significant outcome of the ‘long’ Second World War (1931-1953) was the ‘the volcanic eruption of the American nation state and the consolidation of its new, if qualified, hegemonic order’ (p. 3). The four papers ‘de-exceptionalised’ US aid, while at the same times envisioning the consolidation of American hegemony. They highlighted tensions and frictions which emerged over the giving and receiving of aid, examining issues around expectations and management of gratitude. The seminar was attended by 24 participants, drawn from the UK, France, Italy, Norway, the US and Australia.

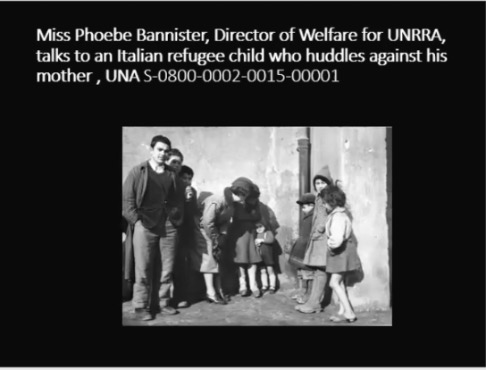

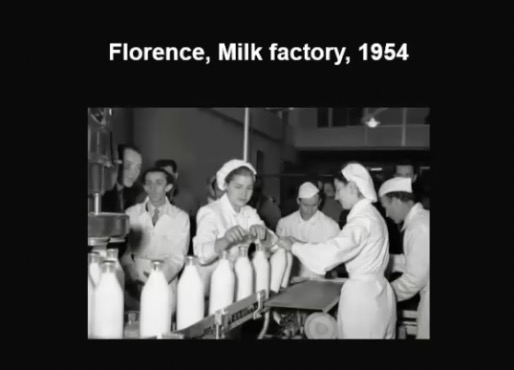

Silvia Salvatici (University of Florence) opened the session with a fascinating paper on food aid and nutritional sciences in post-war Italy, demonstrating how the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration [UNRRA]contributed to the modernisation and development of the modern welfare state in Italy. She showed how the mission of UNRRA shifted from collecting information about non-Italian Displaced Persons in this ‘ex-enemy’ country (1944) to the rehabilitation of agriculture and industrial plants (August 1945) and an extended welfare programme. The American government was influential in this process of transition from ‘mere relief’ to ‘true rehabilitation’, putting pressure on other UNRRA member states to allow certain categories of Italian civilians (particularly children and pregnant women) to be included in the organisation’s programme. In American UNRRA planners’ term, rehabilitation meant to support the development of the modern welfare system so that local organisations could provide people in need in the future and support new ‘truly democratic’ institutions. Silvia shed lights onto the issue of Italian ‘cultural resistance’ to the products distributed by UNRRA. UNRRA relief workers often complained that Italians were unable and/or unwilling to cook the food deliver to them (dislike condensed milk, dried soup, etc) and were ignorant about nutrition (resulting in the exacerbation of their malnourishment). For Silvia, the issue of feeding, welfare and nutrition reveals under-studied connections between post-war relief and the social, economic and cultural changes that took place in the first years of the Italian Republic.

In the following paper, Daniel Maul (University of Oslo) explored the tensions of Quaker humanitarianism through an examination of Anglo-American Friends’ medical collaboration in the “China Convoy” (1941-1951). Created by the British Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU), the Convoy’s main aim was to deliver medical supply over the so-called ‘Burma road’ and, after 1942, provide medical services in mobile clinics for the Chinese army and civilians in Western China. While Americans were never the most numerically important group in this unit, with time they provided most of the funding and eventually took over its leadership. The Convoy was international (with a growing number of Chinese workers) and its members had different gender and religious backgrounds (10% of women, 50% of Quakers). In his paper, Daniel focused on American internal discussion and the ‘geopolitics’ of humanitarian service, showing how despite the ‘pacifist’ commitment of most of its members, the convoy was unequivocally part of the war effort. He also emphasised the tensions between British and American Quakers, resulting from American perceptions as to their ‘professionalism’ clashing with British ‘amateurism’ and what many saw as the imperialist undertones informing the convoys initial work. Using the word of an American Quaker, Daniel summarised one rather pragramatic rationale behind the eventual cooperation despite of this tensions with this line: ‘we have the money, but they have the access’. According to Daniel, the main reason behind American involvement and increase funding however was the notion of ‘constructive service’ and American Quakers’ effort to repeat the experience of the First World War’s Quaker relief and reconstruction units working behind the frontlines in France. Seen from this perspective the dangerous convoy seemed to provide an opportunity to render exactly the form of alternative service that could be framed as being humanitarian and pacifist at its core in line with Quaker values and at the same time convey an image of highly sacrificial and patriotic committment.

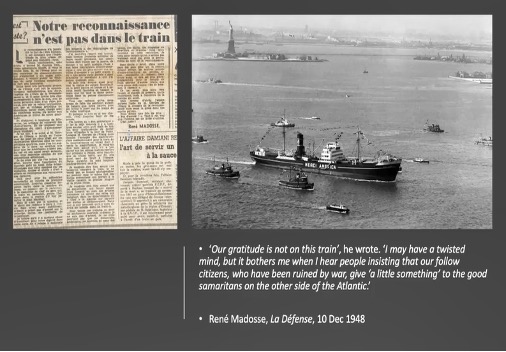

In her paper “American humanitarian aid and (in)gratitude in post-war France”, Ludivine Broch (University of Westminster) explored political and emotional expectations of those giving and receiving American aid after the Second World War. This reflection is part of her current project on post-war Franco-American relations. In this paper, she focused on the “Friendship train” that left San Francisco in November 1947 and travelled across the United States to collect food, clothes, and medicine – and then redistribute them in France and Italy. This initiative took place in the long history of American philanthropy which goes back to the late 19th century and increased significantly during world wars and their aftermaths. Relying on private donations, the train was enthusiastically celebrated by the American press, which emphasized how grateful France was – showing that private relief was a vehicle for gifts with an expectation of return: it created a bond which needed to be acknowledged. Beyond this popular narrative of American generosity and eternal gratitude, Ludivine demonstrated that the relationship between givers and receivers of aid was much more complicated. Drawing on archival material that paints a different picture than that offered by the press, she drew our attention to the gap between such expectations and the reality of people struggling to receive aid. Indeed, rumours and discontent accompanied the train’s journey through France: even if active ingratitude was rare and could be politically motivated, receiving aid provoked mixed feelings – shame being one of them.

Julia Irwin (University of South Florida) concluded this thought-provoking session with her paper ‘War and Peace? ‘Peacetime’ Humanitarian aid In the Shadow of the Long Second World War’. Julia’s forthcoming book focuses on American aid after natural disasters during the 20th century. By replacing the Second World War in a broader context, she argued that the conflict transformed both American and international humanitarian practices far beyond the war itself, having a profound impact on peacetime activities. The United States involvement in the Second World War left it unrivalled in its command of humanitarian logistics. This had crucial implications for the international disaster relief system. To quote Daniel Maul, the period between 1917 and 1945 saw “the rise of a humanitarian superpower”. Part of this process, Julia argued, was the expansion of American military power, which allowed the United States to project its humanitarian power more effectively. While many countries received aid from the US army after natural disasters in the early 20th century, the long Second World War was a turning point. After 1930’s had showed early signs of changes, the 1939-1945 years were decisive: the increase of the US army’s manpower, fleet, and military bases around the world was then reinvested in natural disasters relief. Between 1945 and 1953, these wartime developments became entrenched, the US Army responding to dozens of catastrophes all over the world. In sum, Julia demonstrated that American mobilization for the Second World War extended the United States humanitarian reach – which also served multiple diplomatic, strategic, and economic objectives. This, Julia concluded, invites us to further question the relationship between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power and the lines between wartime and peacetime aid.

Presentation slide, Julia Irwin, ‘War and Peace? ‘Peacetime’ Humanitarian aid In the Shadow of the Long Second World War’

These four papers were followed by a lively and stimulating discussion about American power and about the subtle forms of resisting it, contesting the narrative that Americans told about themselves (even in the most mundane way by complaining about the quality of American flour or chocolate) and re-negotiating aid. We discussed the role of gender in these power relationships and renegotiation processes, the question of gratitude management (and distribution of manuals to ‘show gratitude in the right way’) and the necessity to think about ‘languages of entitlement’ (Jessica Reinisch).

Further reading:

Susan Armstrong-Reid China Gadabouts. New Frontiers of Humanitarian Nursing, 1941-1951 (Vancouver: UBC press, 2018)

Julia Irwin “Disastrous Grand Strategy: U.S. Humanitarian Assistance and Global Natural Catastrophe,” in Rethinking American Grand Strategy, eds. Elizabeth Borgwardt, Christopher McKnight Nichols, and Andrew Preston (Oxford University Press, 2021): 366-383.

Daniel Maul The Politics of Service. US-amerikanische Quäker und internationale humanitäre Hilfe 1917–1945 (De Gruyter, 2021, open access and available here).

Silvia Salvatici A History of Humanitarianism 1755-1989. In the name of Others (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019).

Jessica Reinisch ‘ ‘Auntie UNRRA’ at the Crossroads’, Past and Present, 218, 8 (2013), pp. 70-97.